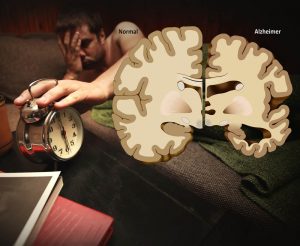

Individuals affected with Alzheimer’s disease exhibit a marked disruption of normal circadian patterns.

These are most noticeable as disruptions of sleep. Many individuals in the early stages of dementia become unable to sleep at night. As a consequence, they may be drowsy during the day. Some become very agitated and restless in the early evening or late afternoon (“sundowning”). As the disease progresses, patients become more wakeful at night and sleep more during the day, sometimes to the point of completely reversing the normal human wake-sleep cycle. Trying to deal with these sleep disruptions is one of the more difficult aspects that caregivers struggle with, and is one of the major reasons why Alzheimer’s patients are moved into institutions.

Why Sleep Disruptions?

The hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is thought to be the master clock of the human body. It sits in the brain near where the optic nerves cross. It receives input from the eyes about light levels. When it detects low light levels it triggers the pineal gland to secrete melatonin, a hormone that makes people sleepy and helps to coordinate the body’s circadian rhythms. Many of the body’s functions follow circadian rhythms. The most obvious one to people is the sleep-wake cycle. Autopsy studies of Alzheimer’s patients usually find that there has been significant degeneration of the SCN in the later stages of the disease. However, even in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s, there is obvious dysfunction of the SCN and disruption of rhythmic melatonin production.

Does Sleep Disruption Cause Alzheimer’s?

Bright Light Therapy?

Initial studies of bright-light therapy to treat patients were somewhat inconclusive, but after a more statistically correct way to analyze data from activity studies was established, the field forged ahead. Exposing Alzheimer’s patients to strong light throughout the morning was found to improve normal sleep cycles and improve the mood and behavior of the patients. However, the patients needed months of daily treatment before a clear response was seen. Healthy adults with sleep disorders respond to similar light therapy in two weeks or less. The researchers speculated that lack of sensitivity to light may be in part the cause of the sleep disorders observed in Alzheimer’s disease. In an interesting twist, in a study published in Chronobiology International, researchers attached sensors to institutionalized Alzheimer’s patients and simply recorded the amount of light they were exposed to and their degree of activity. They found that most of the patients were exposed to continuous levels of very dim light with no apparent changes throughout the day and night. Some patients were exposed to more light at night than during the day, and these patients tended to show no circadian pattern in their periods of agitation. These types of conditions in institutions are unlikely to assist patients in re-developing circadian rhythms. Thinking that imposing a more structured sense of daytime on Alzheimer’s patients might help them re-establish a better sense of day and night, one group conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing no intervention to a combination of morning bright-light therapy and outdoor walking for 30 minutes each day. It was thought that the morning bright light plus exposure to natural daylight every day and healthy exercise would help normalize the circadian rhythms of the patients. For patients who consistently engaged in both walking and light therapy, there was a slight increase in nighttime sleep, but the effect was not dramatic.

Stimulating Melatonin Production

The SCN establishes circadian rhythms primarily by stimulating melatonin production. If the SCN is only sluggishly responding to light in Alzheimer’s patients perhaps directly administering melatonin to patients might do the trick.

Both Bright Light and Melatonin

Obviously, combining bright light therapy and melatonin is the next step. A study that combined bright light therapy in the morning with oral melatonin in the evening found the combination to be reasonably effective in improving daytime waking and activity in institutionalized Alzheimer’s patients. The next step is to try the combination treatment on early-stage Alzheimer’s patients who are still living at home. An even more interesting experiment would be to see if bright light therapy (with or without melatonin) could prevent at least some cases of Alzheimer’s in elderly people suffering from sleep disorders.