Human beings are creatures ruled by rhythms. The chemical tides of our bodies are constantly ebbing and flowing in a complex pattern of overlapping cycles. These cycles are responsive to a number of environmental factors from the amount of sunlight we receive to what we have for lunch each day. In fact, we are so bound to these cycles that an entire branch of biology has been dedicated to the study of them: Chronobiology.

By better understanding the various intrinsic rhythms by which our bodies regulate themselves, we can more effectively treat disorders that either disrupt these rhythms or are the direct result of a disruption. Along these lines, circadian sleep disorders, which manifest in a variety of ways, are one such group of disorders that scientists give special scrutiny.

Circadian Rhythms

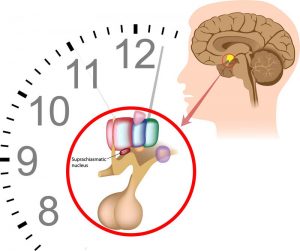

The circadian clock itself is set primarily by light cues that are received by special receptors in the eye and which run along channels in the brain to the SCN. However, the human body uses other time cues, such as periods of exertion and meal times, to synchronize this clock as well. Those activities are rife with hormonal and energy fluctuations, the release or absorption of sugars in the blood and the rise and fall of cellular metabolism. Hence, that midnight snack is actually a much more complex undertaking than the simple trip to the fridge it seemed to be on the surface.

What is a Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder?

A circadian rhythm sleep disorder can be defined as any disruption of the body’s internal clock, an inability of the body clock to entrain each 24-hour period or a discrepancy between a person’s inner clock and the environment around them. People who have such a disorder may experience one of the following problems:

- sleep is not refreshing or restorative

- insomnia, difficulty falling asleep or daytime sleepiness

- chronic sleep disturbances such as frequent waking or waking too early and being unable to go back to sleep

- significant impairment to the mental, emotional, physical, social, occupational or educational performance

Common Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder (DSPD)

Advanced Sleep Phase Disorder (ASPD)

Typically experienced by older adults, this disorder is essentially the opposite of DSP and is associated with “morning people” who wake two or more hours earlier than is considered normal — between 3 a.m. and 5 a.m. — and prefer to go to bed between 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. Many who experience this disorder are middle-aged, and the incidence of ASPD has been seen to increase with age. If they are allowed to adhere to their preferred sleep schedule, their sleep patterns are extremely stable.

Irregular Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder

Irregular Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder involves inconsistent sleep patterns with no correlation to day-night cycles. Those who suffer from this disorder typically have trouble falling asleep and staying asleep in addition to daytime sleepiness. This sleep disorder is most commonly seen in people with neurodegenerative health conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease or Parkinson’s Disease.

Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder

With Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder, the body’s internal clock fails to reset, resulting in a consistently shifting sleep-wake cycle. Insomnia and daytime sleepiness are often symptoms of this disorder, which primarily affects those who are totally blind. In fact, nearly 50 percent of this group experiences Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder.

Shift Work Disorder

This is commonly experienced by those who work late night or early morning shift jobs. It is associated with feelings of sleepiness at work and an inability to sleep during the day and early evening when most others are awake. People who prefer diurnal (daytime) activity may be especially vulnerable since their natural inclination is to be awake during the day and sleep at night.

Jet Lag

Flights that pass over multiple time zones can cause a condition commonly known as jet lag, wherein a person’s internal clock must reset itself in relation to the local time. Symptoms of jet lag include trouble falling asleep and staying asleep and daytime sleepiness. Jet lag sufferers can experience symptoms for up to a week or two after travel.

Prospective Treatment Regimens

Lifestyle Changes

Lifestyle changes that may improve symptoms of certain sleep disorders include adjusting the amount of exposure to daylight, changing the timing of the normal daily routine — such as exercise and meal times — and implementing a scheduled nap or naps during the day.

Bright Light Therapy

In bright light therapy, for brief durations during the day, an individual is exposed to safe levels of intense, bright light. This is thought to help encourage the reset of the body’s circadian clock.

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep hygiene involves education about how to encourage healthy sleep habits, such as avoiding television and computer screens at least an hour before attempting to sleep, avoiding self-medication through drugs and alcohol, and how activity and nourishment schedules interact with circadian rhythms.

Melatonin

Produced naturally by the brain at night, this hormone appears to play a part in regulating the circadian cycle. With melatonin therapy, patients are prescribed regulated doses of melatonin at specific times.

Understanding how the circadian rhythm impacts and is impacted by both lifestyle habits and underlying physiological and environmental factors is crucial to helping individuals attain relief from sleep disorders. It may help some to know that they can make tremendous impacts on their quality of sleep simply by avoiding the stimulating light cues sent by computers and televisions, which tell the brain to wake up. However, sometimes more intensive therapies are necessary to alleviate a more serious circadian disruption.

What is most important to remember when tackling these disorders is that until a bit over a century ago, humans did not have electricity in their homes. Additionally, until the industrial revolution, the demands of the workplace ran along very different lines. The era of modern technology and industrialized working ideologies, such as overtime and “workends,” are extremely new.

By comparison, our brains, the SCN, the circadian clock and our need for sleep are very old. As with the diagnosis of unknown allergic reactions, eliminating the probable causes of sleep disorders is the most prudent course. While medication may be in order, practicing good sleep hygiene, adjusting life routines and exploring safe alternative therapies may yield incredible results.